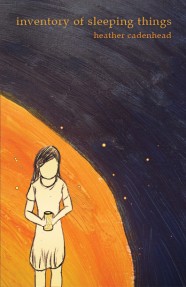

Today I’m super-excited to share with you the poetry of Heather Cadenhead, a great friend and co-worker. Heather recently released her very first chapbook called Inventory of Sleeping Things. So I know what you’re thinking. What the heck is a chapbook? I asked that, and a bunch of other questions of Heather, who kindly agreed to answer them.

And as an added bonus, I’m giving away a copy of this exceptional poetry collection. Just leave a comment on this point by next Friday, and then Heather will pick a winner at random. (And if you’re not a poetry fan, still enter because there’s probably someone in your life who would love this as a gift.)

1. Heather, your first chapbook is called Inventory of Sleeping Things. Explain to us what a chapbook is.

As best as I can tell, chapbooks originated sometime in the sixteenth century. They began as inexpensive booklets for the working class, featuring everything from short stories and folk plays to religious or political content. The term comes from the peddlers, or chapmen, who sold these little books. Most chapbooks were purchased by those who couldn’t afford to keep formal libraries. Their popularity decreased in the 1800s but, in the 20th and 21st centuries, we’ve seen a sort of revival of the chapbook. I think self-publishing played a huge role in reviving the format, but now, we see many small presses who publish chapbooks exclusively, and the reason for that, I think, is  because they’re not terribly expensive to produce, so they really sustain a lot of the work that small, independent presses are doing. Mainly, you’ll see poetry chapbooks—short books with anywhere from 20 to 40 poems—but I’m seeing a lot more short story chapbooks these days, too. I think it’s an interesting format—one that digital publishing has expanded even more. It’s not uncommon at all to see digital chapbooks, or “e-chaps,” these days. I think it continues to be a format that is kind to poets who are just starting out, and allows us to build a small repertoire of publishing “cred” that’s helpful when we start seeking publishers for full-length poetry collections.

because they’re not terribly expensive to produce, so they really sustain a lot of the work that small, independent presses are doing. Mainly, you’ll see poetry chapbooks—short books with anywhere from 20 to 40 poems—but I’m seeing a lot more short story chapbooks these days, too. I think it’s an interesting format—one that digital publishing has expanded even more. It’s not uncommon at all to see digital chapbooks, or “e-chaps,” these days. I think it continues to be a format that is kind to poets who are just starting out, and allows us to build a small repertoire of publishing “cred” that’s helpful when we start seeking publishers for full-length poetry collections.

2. Where did your title come from?

I got the title from “After Hours,” the last poem in my chapbook. The last two stanzas read: “Here, I make an inventory of sleeping things: / you; our next-door neighbor, five tabby cats / curled up at her feet; the brown-eyed dog / we brought home from the pound. Tell me / why you closed your eyes. Because / you could, I think, is the answer.” There are a lot of poems about night, a lot of poems about dreams. I see a sort of “Wee Willie Winkie” thread running throughout the poems—I just feel a sense of awe when I observe the beauty of nighttime, and feel most aware of the mystery, and majesty, of creation. There’s this sense of hushed reverence peppered with questions: How did I get here? Am I loved? There’s not always an obvious answer to every question—as it is with life. In our limited understanding of God, there’s always going to be mystery. I see congruence in my thoughts about God, and my total dependence on Him, with a poem like “Illiterate,” where I talk about a girl who can’t read: “Dear Baby my mother wrote me a month before I was born. / I recognize her curves, her jagged signature, but it’s still / Sanskrit to me. I only know it says baby / because my father told me once.” In the same way, I see myself as an unlearned child—and the only things I know in this life are “because my Father told me,” because not one sparrow falls to the ground apart from Him.

3. How long have you been writing poetry?

I’ve been writing poems since I was probably eight or nine years old. I would write poems for my mom on Mother’s Day and that sort of thing. When I was in high school, I wrote poems about boys. I think it began as a way to express myself lyrically. In college, I had to “relearn” poetry—and go from the “Dear Diary” approach to more of a focused, craft approach, if that makes sense. I’ve been working at poem-writing as a craft—as opposed to an outlet—for about five or six years now.

4. What’s your favorite poem in Inventory of Sleeping Things? What’s it about?

If I had to pick a favorite, I’d probably go with “A Man Names Things” because it was so much fun to write, and hopefully it’s fun to read, too. I’ve had a lot of my poet friends call it a feminist poem, but really, it’s about a desire for acceptance, and the temptation that comes with being able to read another person—knowing what they expect of you, what they’d like for you to be—and sometimes giving into that, and going with that, rather than being who you truly are. And then, it’s about how arduous it can be to reverse someone’s perception of you once you’ve allowed them to think something that wasn’t perhaps entirely true. A close second would be “Raven,” which was inspired by Ruth 1:16: “But Ruth said, ‘Do not urge me to leave you or to return from following you. For where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God.’”

5. Your day job is in the fiction department of a major Christian publisher. Have you ever considered writing fiction? If so, what would you write?

I’ve most definitely considered writing fiction! I think fiction is great fun—I love reading it, and I love experimenting with the occasional short story. If I ever wrote a novel, I’d be interested in doing a coming-of-age story, I think, because those are the kinds of stories that jump out at me the most. I’d love to set something in the ’80s—I think it was such an interesting decade, and not just because I was born in it. The ’80s had spunk.

6. Where can our readers purchase your book?

You can purchase Inventory of Sleeping Things at www.maverickduckpress.com. Or you can email me at heathercadenheadATgmailDOTcom.

Thanks for joining us, Heather!

Okay, readers. It’s up to you now. Leave your comment for a chance to win.